Back in middle school I was really into trading cards and tabletop role-playing games. I wasn’t so interested in the escapism or even the gameplay. I loved the calculated preparation that took place before games were played, diving into deep pools of possibility and surfacing with creative combinations that leveraged the rules of the game. I pored over stacks of cards and handbooks to build unique, strategic decks and compelling characters. In competitive debate, I dove deeper, skimming research to consolidate excerpts into cases that I could argue confidently. I found the preparation exhilarating. Though I never identified much with the Boy Scouts, I tried to live by their motto: be prepared.

When the time came to start thinking about college, I set my hopes set high, on big-name schools with low acceptance rates. Sticking to the familiar, I took to strategic preparation, but I could see right away that this wasn’t going to be the same sort of game; these dives were introspective, these stakes real; I wasn’t creating a character, I was presenting myself. Filling out applications, the pools of possibility seemed murky and miles deep; I didn’t know what to look for and leverage because I couldn’t discern all the rules of the game. When I had trouble gauging my own depths, I immersed myself elsewhere to prepare, looking at statistics and scattergrams and college message boards until my eyes hurt. I wrote calculated essays that probably hurt my chances, sacrificed sleep, sanity, and self-esteem, studying for an exam with no right answers. I prepared, but I wasn’t ready; I don’t know that I could have been. Preparation is just a checklist, readiness is a state of mind.

In Man’s Search for Meaning, Viktor Frankl wrote of death, “with the end of uncertainty came the uncertainty of the end”. This was how waiting for decisions felt for me, a little like waiting to die. With cyclical anxiety, trepidation, and expectation-management, I awaited my diagnosis. On the night that decisions came, I made sure that I was in a car when I opened them, windows down on the freeway, so no written words would linger in stagnant air as I sat still. Car driving, mind racing, after so much waiting, opening each of them was like ripping off a band-aid. There had been insurmountable uncertainty and, with a few “Congratulations…” and plenty of “We are sorry….” and “Due to…”, my options were suddenly set out before me.

All that had been out of my control became a decision only I could make. My uncertainty gnawed at me until pending deadlines forced me to choose. I chose, and so knew, with total certainty, that I was going to the University of Wisconsin, Madison. And, like finding out I was going to die, the end of my uncertainty brought only the uncertainty of the end. I don’t mean to be morbid; admissions aren’t something to be mourned; they are as much a beginning as they are an end. But for my high school self, it’s also true that college was the light at the end of the tunnel, a finality to be achieved, not lived through.

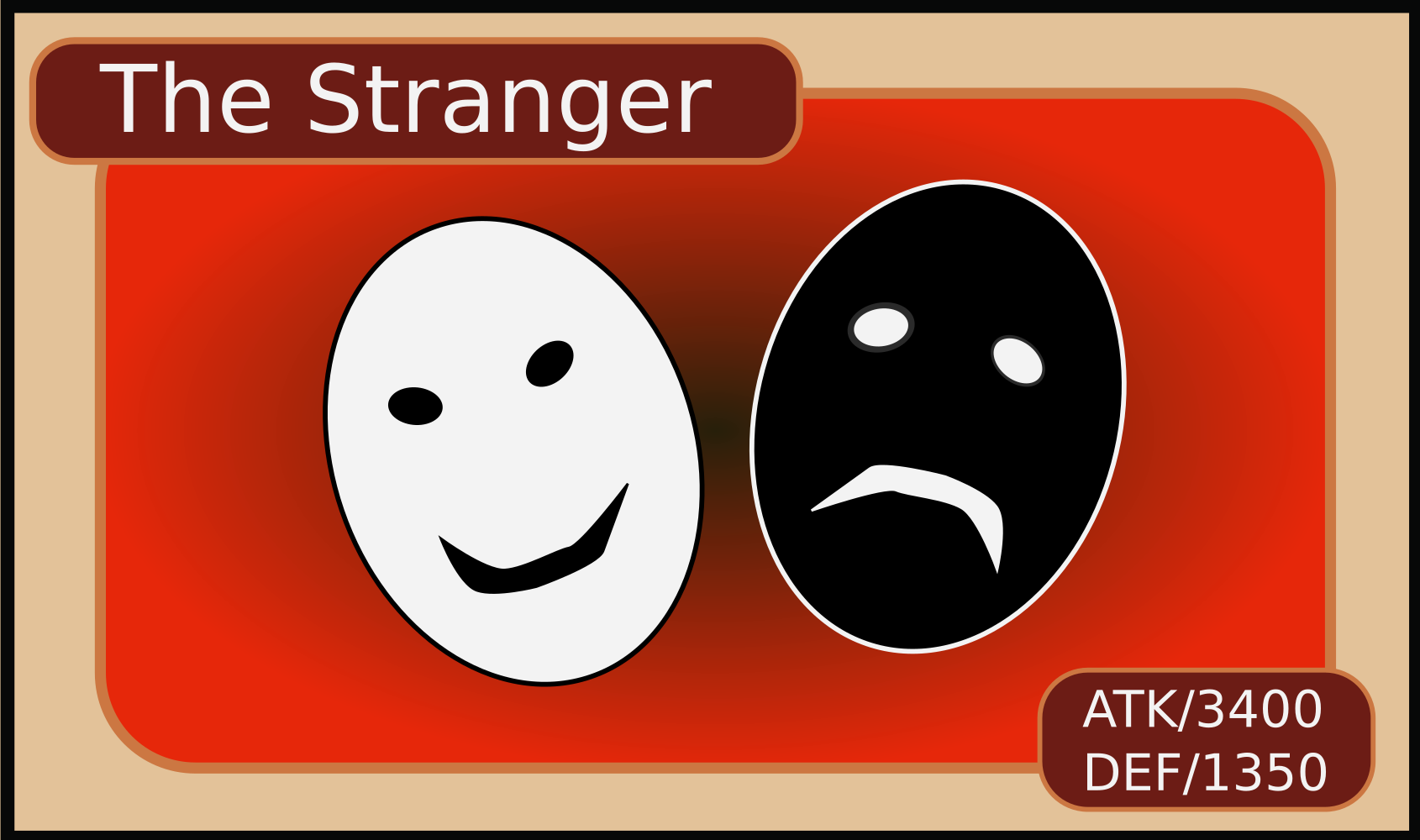

For all my research, I hadn’t a clue what college would actually be like. When asked if a school would be a good fit for me, I would imagine myself there, what I would do, how I would spend my time, who I would spend it with. But my hypotheticals were never me. College was foreign and I knew that it changed people, so I believed that these people I dreamt up were utter strangers. Knowing at last where I would go to school, I felt like I was on the last lap of a relay, my only job being to pass the baton. I would become a past life, and the next part of the race would be up to my future self, a stranger, older, wiser, and faster than me.

The University of Wisconsin Madison seemed like a great school, but while it met all my basic criteria, it was far from my first choice. I felt that I had let myself down. I had spent the months before decisions worrying excessively about my future and the months after in regret, convincing myself of every way that I had been inadequate. There’s a fine line between learning from mistakes and being consumed by them, especially when so little feedback is given to guide reflection. I like to think that, if time is linear, and every second’s experience is a ray shooting out from that line, then the fullest life is lived orthogonal to time, not always peering into the past nor predicting the future, but being present. The present had been foreign to me then, swept away by hypotheticals that rang like songs stuck in my head, by “how did”s and “what if”s and “if only”s.

I had once thrived in exploration and creativity, deep in pools of possibility, but, during my senior year, preparation had needlessly turned to worry and self-degradation. Diving into waters as dark as admissions’ black box, I had forgotten to come up for air, to breathe in the elation that can exist above as below, in mind-wandering, and silence, and self-indulgence, and activities done for their own sake. I missed those parts of life free of competition, self-doubt, and pressure both external and internal. The summer after high school, I resolved not to let myself drown or be crushed by that pressure, to spend more time in the present and find contentment. At Madison, I found it.

The handoff of the baton went smoother than I had expected, as if life and death were some seamless transition. In my first weeks at Madison, I stopped running in circles and instead slowed to catch my breath. I made new friends, stayed in touch with old ones, and let life speed up naturally around me. I loved exploring the campus, its hills hiding districts diverse in architecture and era, from red tile roofs to the hypermodern. It’s an academic labyrinth with urban and natural environments packed tightly between between city and shore.

After about a month, I received the opportunity to participate in research on the origins of life. I had never taken a class in biology let alone done research on its genesis. When researching colleges, this sort of thing had never been part of my search criteria and yet, it’s been the most fulfilling aspect of my time in college so far. Conducting research alongside professors and post-docs, I found camaraderie that I had never expected; the hierarchy I had expected collapsed under the weight of curiosity and common cause. People from different stages of life, different backgrounds and disciplines, learning together, I felt the opposite of my high school self. I could glimpse the day-to-day lives of grad students, faculty, and other friends and none of it seemed so distant; whereas in high school, college had been unknowable, breeding uncertainty and all its ails, here I could experience and understand the trajectories my life might take. College’s breadth of collaboration and depth of discovery gifted me with contentment where I had once lacked certainty. So too, the idea of college as the final means collapsed to college as the first and brilliant colors flooded future sight.

I didn’t get into my top school, but now I can’t imagine myself anywhere else. I’m here, not just content, but truly happy. Best of all, I see that my trajectory is my own. Though I can’t see everything in front of me, I’m not blind either. No decision that I made in high school defined my life; I’m not an arrow that’s been shot or a baton passed. College changed me, but I’m no longer running someone else’s race. I am my own anchor, running ahead, choosing the placement of my feet. Best of all, I am no longer a stranger to myself.

Alex Plum is a freshman at the University of Wisconsin - Madison majoring in Engineering Physics, Mathematics, and Computer Science. Hailing from Milwaukee Wisconsin, he enjoys good books, long runs, deep questions, and seeing sunsets over water. He looks forward to a lifetime of learning, connecting and creating with others.